This post is a high-level overview of efforts to reverse engineer neural networks (not mechanistic interpretability as a whole). Aimed at people who are familiar with neural networks, but not necessarily any bits of mechanistic interpretability. And while the most interesting models we have right now are transformers, I'll use the term "neural networks" as I think most of this generalizes. I'll also do my best to reserve the word "model" to mean "neural network" and "explanation" for "explanatory model of how a neural network works."

Why reverse engineer neural networks?

In previous years we had specialized models that could play games at a superhuman level or predict protein structure; we now have powerful models that can do many tasks via in-context learning. And while their capabilities are jagged, both the average and the peaks are still impressive, and quickly rising.

I believe these models are able to perform these feats because they've learned sophisticated algorithms that generalize well. There's a fair amount of evidence for this. My intuition is that models are basically incentivized to compress the internet, and generalization is much better than memorization in terms of efficiency (which models care a lot about, because the internet is quite big, and they have a relatively small set of parameters to encode information).

These models are being used more and more, often as chatbots or instruction-following agents. We're already observing issues though, such as sycophancy in chatbots, how ridiculously easy it is to use prompt injection to hijack agentic behavior, and initial signs of deception and other naughty things.

The main value proposition of reverse engineering neural networks is that if we can understand the internals we'll be able to look at the specific bits related to these issues and either intervene, or develop better safeguards. We may even be able to make formal guarantees about what types of behavior a model will engage in under some set of inputs.

And beyond safety/control, it's an alien intelligence! And the closest thing we have to a human brain that we can easily poke and observe right now. We know very little about how our own intelligence works at a low level. Maybe there are certain parallels to discover about how graphs of neuron-like things perform computation?

What kind of explanation do we want?

The goal of reverse engineering is to find an explanation that predicts the model's behavior. Fundamentally, we want this explanation to satisfy two properties:

- The explanation should be faithful. It should predict the model's output as much as possible.

- The model should be understandable. Humans need to be able to grok the explanation and reason with it.1

These properties are fundamentally in tension. As humans, we can only hold a few things in our heads at once, and therefore need explanations composed of fewer (higher-level) parts to be able to reason about things.

An explanation at one extreme of the faithful-understandable spectrum is "the model uses these weight matrices to perform such and such series of matrix multiplications and some nonlinearities to produce a probability distribution over the next token." This explanation is very faithful. In fact, it's the canonical model: for whatever input you hand me, I can perfectly predict the model's output. But "apply this series of matrix multiplications" doesn't tell me anything about what the model is really doing. For questions like, "What will the model do on inputs containing requests for instructions to make a bioweapon?" this explanation isn't useful. That set of inputs is too large to enumerate over, and staring at the weights isn't going to help me.

An explanation at the other extreme is "the model is instruction-following." Humans are great at reasoning about entities that are goal following, so this explanation is easy to understand. But the faithfulness is low fidelity. For the bioweapon request question, this model would predict "yes," but this might be incorrect if the model has had any amount of refusal training. 2

What do we know about how neural networks compute?

So we'd like a high-fidelity model of neural network behavior that we can understand. It's not immediately obvious to me if it's reasonable to expect we can get this. It seems like it relies on the assumptions that

- Neural networks (trained with gradient descent) will land on weights that are human-understandable given some explanation.

- It's possible for us to reverse engineer the model into such an explanation.

Maybe gradient descent has some mathematical/structural reasons to choose models that are simpler or more decomposable (and hence more human understandable)? One intuitive argument is that algorithms that generalize tend to be more understandable than memorization (which will yield giant opaque lookup tables), and the reason neural networks are popular/effective is because they generalize.

Models represent (many) things "linearly"

There is a lot of evidence that neural networks represent concepts, called features, as "linear" directions in activation space. For example, we can train a linear model, called a linear probe, on model activations sampled from forward passes to predict a $1$ when the input is in English, and a $0$ when the input is in Arabic. Experiments show that this linear probe will do very well, and we can often take the direction that it learns as an "English text" feature in the model, a direction that represents when the input is in English. We might even be able to artificially inject this direction into the model's activations during a forward pass to trick it into producing English text in a context when it otherwise wouldn't (this is called steering).

In this example, our feature is a direction in activation space (a 1d subspace). And while there seem to be many 1d features, researchers have also found higher dimensional subspaces that still act like what we mean by "linear feature." A useful definition says that "linear" features are linear in the mathematical sense in that they have two properties:

- Composition as addition: we can combine feature vectors meaningfully by adding them.

- Intensity as scaling: the intensity of a feature is the magnitude of the vector.

These properties can hold for 2+d feature manifolds just as well as 1d subspaces. I'm going to keep using the word "direction," as I think it feels more concrete, but feel free to replace each instance with "low dimensional subspace."

Why does it make sense for neural networks to represent features linearly? My intuition is that neural networks have an incentive to perform computation on many "variables" and the natural unit for this is low-dimensional subspaces that have these composition and scaling properties. Representing a concept as a direction means the model can easily read in the magnitude of that concept via a dot product, and can similarly write out to features simply.

This claim that neural networks represent features linearly is called the Linear Representation Hypothesis. It's useful to break it into weak and strong versions:

- Weak Linear Representation Hypothesis: Some/many features of neural networks are linear.

- Strong Linear Representation Hypothesis: Most/all features of neural networks are linear.

And while the evidence for the weak version is quite strong at this point, with all the dark magic and messiness that seems to be going on inside neural networks, it's still unclear whether the strong view is correct.

Models superpose these representations

So neural networks represent many features as directions in activation space. But activation space typically has dimensionality on the order of 10,000 (and hence can only allow 10,000 orthogonal directions), and models clearly represent (much) more than 10,000 concepts. What's going on here?

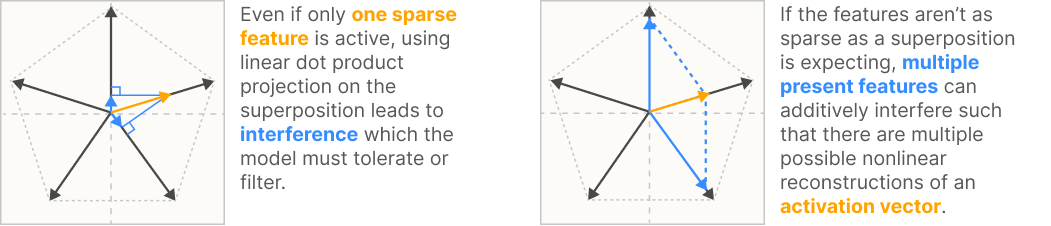

It's widely agreed that models perform superposition, a phenomenon where models use linearly dependent feature directions. They're able to get away with this without too much performance loss due to interference for a few reasons:

- High dimensional vector spaces have exponentially many "almost orthogonal" (cosine distance below some epsilon) vectors. This makes the interference relatively small, which nonlinear activation functions like ReLU can zero out by placing it below their threshold.

- In realistic training distributions, features are very sparse: only a relatively small handful of features are active for any given data point. The feature for "person has hairy armpits" probably doesn't co-activate much with the "nails on chalkboard sound" feature, so, in expectation, the model doesn't take that much of a hit in the loss by making their directions slightly linearly dependent.

If you train a toy model to take in $n$ features, and then reproduce them after a $d<n$ dimensional bottleneck, you'll find that:

- Without an activation function like ReLU, the model will only represent the most frequently occurring features using $d$ orthogonal directions. Without any way to get rid of the interference, representing more than $d$ features would mean one feature activating would look like other features slightly activating. This interference turns out to be bad enough for the loss that it's not worth doing superposition at all.

- With ReLU, superposition does happen if sparsity is high enough. With low sparsity, the ReLU model acts just like the linear (no ReLU) model. As sparsity increases, the model exhibits more and more superposition.

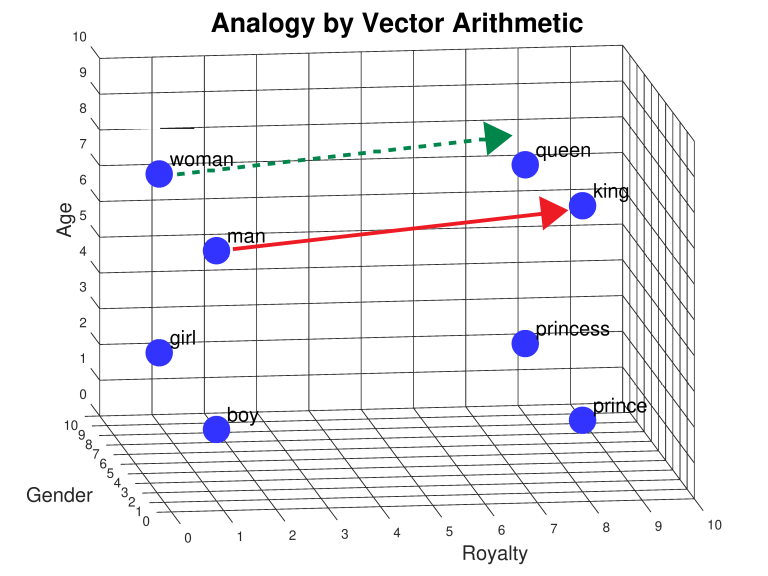

Models use geometry to perform computation

One very well known interpretability finding from word2vec is that you can do arithmetic with word vectors and it often sort of works. Concretely this means I can do something like, $$\text{vector}(''king'') - \text{vector}(''man'') + \text{vector}(''woman'') \approx \text{vector}(''queen'').$$

This can be visualized geometrically as a parallelogram:

Examples like this in transformers seem to be everywhere!

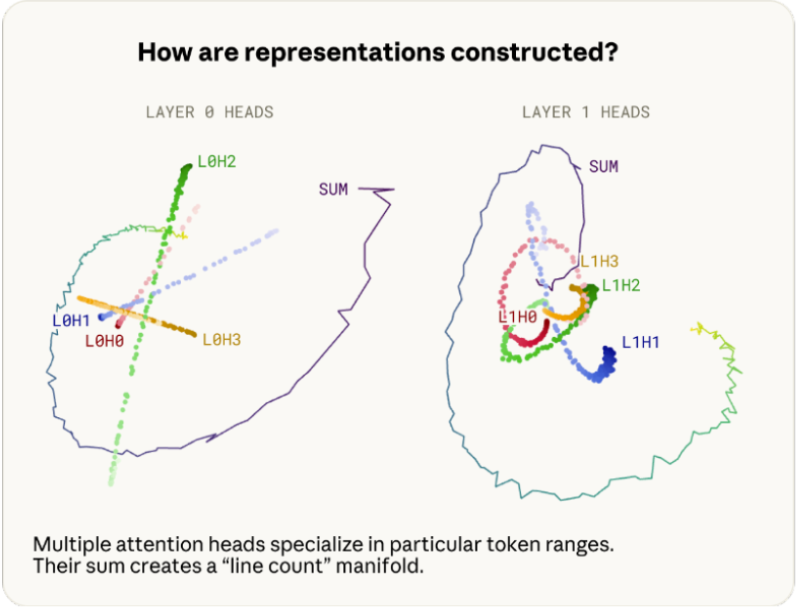

Claude Haiku 3.5 uses a 1d feature manifold to keep track of how many characters into a line each token is:

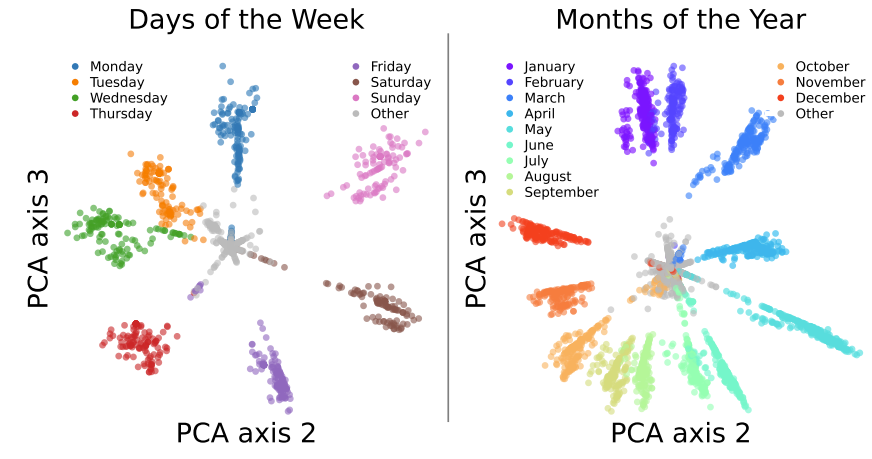

Days of the week and months of the year are arranged, in order, in a circle:

And beyond specific shapes, it definitely seems like semantically similar features are closer together in activation space.

Why are models doing this you ask? Models can be more efficient in their computation and representation by being "smart" about what directions they "choose" as which features, rather than choosing directions only by considering sparsity / interference incentives.

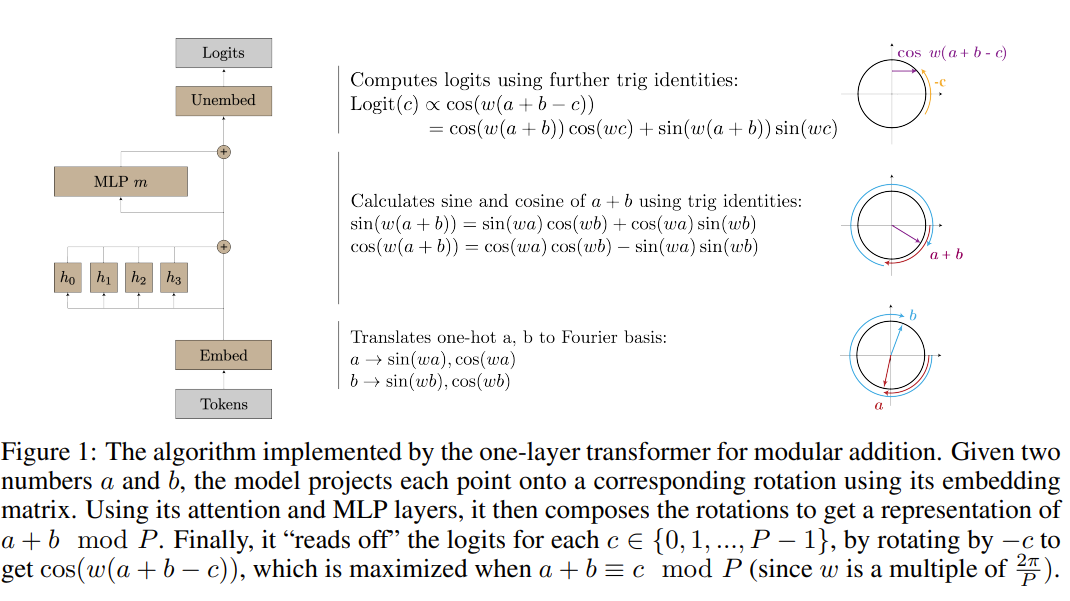

For example, researchers found that a 1-layer transformer trained to perform modular addition works by embedding numbers onto a circle. Then it can perform addition (and get the modulo for free) by composing the rotations described by both features and reading off the result:

Note that this algorithm is more economical in the number of parameters than maintaining a lookup table with an entry for each pair of operands.

Approaches

Given these findings, what are the main approaches to reverse engineer models?

Activation-space decomposition

Starting with a belief in the Linear Representation Hypothesis, it seems like figuring out what each of the feature directions are would be really useful. The main obstacle to doing this is superposition, as it means all of these feature directions are tangled up with each other.

Enter Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs). Their general idea is that you take the activations of the model at a particular layer from forward passes over a large portion of the training set and train an autoencoder on them whose latent representation is higher dimensional than the activations. Then you train the autoencoder with the typical reconstruction objective and also a penalty that incentives sparsity3. This incentivizes the SAE to find directions that can be composed (via addition) in small sets to reconstruct most of the original activation, which we might hope gives us something like an overcomplete basis (read: more vectors than dimensions) of features the model uses.

And this simple idea actually kind of works in practice! If you look at the inputs that an SAE latent activates on the most, as well as the output logits they upweight the most, you'll find that many of them are pretty interpretable. You can find features for things like "base64 string", "DNA sequence", "Text written in Hebrew script."

While this led to a lot of initial hype around SAEs, and a fair amount of hill-climbing on improving and scaling them, their are some serious conceptual issues:

- reconstruction error is low but still significant, suggesting SAEs aren't capturing everything important

- SAE features aren't "canonical" units

- They might pick up features of the data distribution that the model doesn't know about/use

- SAE features ignore feature geometry

- Maybe not all features are easily interpretable by looking at inputs/outputs. Imagine intermediate variables used for something like control flow (ex. counter variable in a loop).

- ...

Generally, people have been struggling to go from SAE latents to a full model explanation and some researchers are moving to other topics.

Parameter-space decomposition

Another (more recent) approach is to decompose the parameters of a model instead of the activations. The inspiration for this is the intuition that models are a combination of many simpler mechanisms bundled together, and that for any particular data point, a small set of mechanisms are (causally) important (sparsity again).

The most recent method here is Stochastic Parameter Decomposition (SPD) which aims to decompose each of the weight matrices of a model into a sum of rank-$1$ matrices, called subcomponents. Subcomponents can then be clustered across weight matrices with other subcomponents they are often "active" with.

This is appealing for a few reasons:

- Rank-$1$ matrices are pretty great low-level units of an explanation. If you view a rank-$1$ matrix as the outer product between two vectors $W=u\otimes v$, then multiplying a vector $x$ by this matrix has the effect of reading the amount of $v$ in $x$ and writing it out times $u$: $Wx=(uv^\text{T})x=u(v^\text{T}x)$. This is simply reading in from one feature stream and writing out to another, which is interpretable and tractable from a formal analysis perspective.

- Because the subcomponents sum to the full weight matrices, the explanation is maximally faithful to the true model (in that it will produce the same results).

The methodology is somewhat subtle, so I'll recommend this lovely explainer (and the paper itself) for a more in-depth treatment.

SPD hasn't been scaled past toy models yet, and there definitely seem to be some methodological and engineering challenges (such as figuring out how to cluster the subcomponents), but I'm excited to see where it goes.

A potential relaxation is "understandable to programs that humans write/understand". Similar to how programmers write programs in high-level programming languages and then trust compilers (which they understand) to lower the code, I can imagine low-level explanations of neural network behavior involving too many factors for human analysis, but still open to attack by programs that we can understand.

You might think we can modify the explanation to be "the model is instruction-following, except for harmful instructions," but this is also lacking in faithfulness. There are tons of edge-case inputs for which the model will give advice on how to construct a bioweapon, and high-level explanations of this sort will always be approximate unless grounded in the lower level mechanics of the model.

Conceptually we'd like the L0 norm to incentivize sparsity, but that's not differentiable, so we use the L1 norm, which has the same effect of driving many latents to 0.