This is a rough note to help me wrap my head around the current answers to the question: "Does SGD have an inductive bias towards simplicity?" Honestly this is a bit of a rabbit hole and I don't feel that I have a cohesive picture yet, but hopefully there are some good pointers here for the interested.

Neural networks trained with gradient descent are great at learning functions from data that can do impressive things like image classification, next token prediction, and predicting the geometry of a protein from its amino acid sequence. But in the space of algorithms that do well on these tasks, some are probably much "simpler" than others. Should we expect stochastic gradient descent to choose simple algorithms?

What do I mean by simplicity?

While there are formal measures of complexity that are interesting, I think something like "minimizes description length / number of moving parts" is generally what I have in mind.

A good example for a complex model would be a look-up table. For example, one way to implement addition is to store the sum of every $(a,b)$ pair for a wide range of inputs.

A simpler model to accomplish the same addition task might have a small lookup table for adding single digits and then compose this with a procedure to add independently along digits and carry overflows when necessary.1

Note that when the underlying task / data has structure, like in the addition case, the simpler algorithm will generalize much better. And a lot of things we care about have a ton of underlying structure (math perspective: for the data-generating distributions we care about, most of the probability mass is concentrated in a manifold with much lower dimensionality than the containing space).

Evidence SGD might bias towards simple solutions

There are a fair amount of people that think that SGD has an inductive bias for simpler functions / explanations of observed data, i.e., it does choose simpler algorithms, everything else (train loss) being equal.

Double Descent

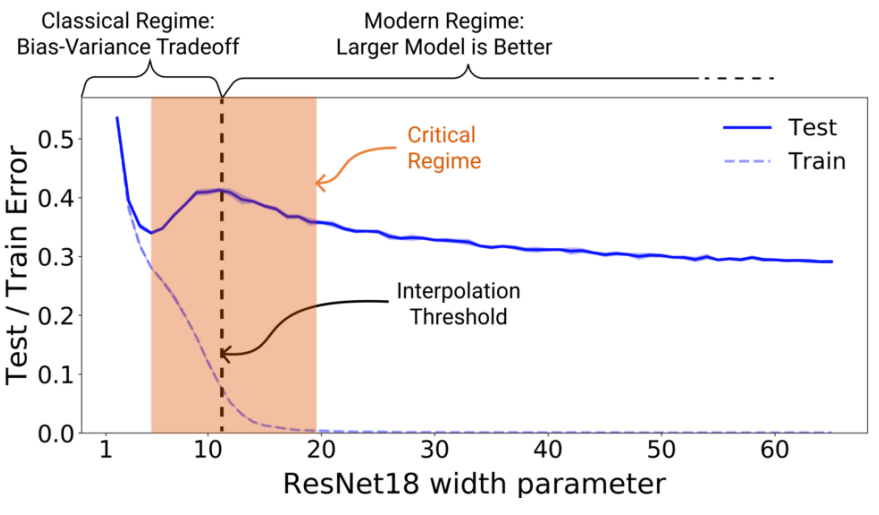

If you train a network of varying size on a task, and plot the train and test error against the model size, there's a fair amount of evidence you'll get a graph like the following (source):

Notice:

Notice:

- Train error is monotonically decreasing as model size increases

- Test error initially decreases, then increases, then decreases again. This funky phenomenon has been dubbed Double Descent.

Why might this be happening? One explanation is that SGD has an inductive bias for simplicity. With that as our frame, this is the story (from SGD's perspective) we can use to explain the graph:

- As SGD begins the first descent, it is using the extra capacity from more parameters to find better explanations for the observed data. These explanations generalize somewhat, as it can do better by generalizing than memorizing with the few parameters it has.

- As the capacity keeps increasing, SGD uses it to overfit/memorize such that the training loss goes to 0. These explanations for the data don't generalize, so the test loss goes up. So far, this is the standard bias-variance tradeoff from classical ML.

- It gets more interesting after you've reached 0 train loss. After this point, if you keep giving SGD more capacity, it is able to find explanations that still achieve 0 train loss, but are simpler. It chooses these because of the (assumed) inductive bias for simple explanations.

- Simple explanations tend to generalize well because it's more likely they're capturing some structure of the underlying data distribution, so we see test error going down again.

Near the "interpolation threshold" (where train error is just going to 0), the model has just enough capacity to achieve 0 training error, but not yet enough capacity to do well at its secondary goal of finding a simple solution.

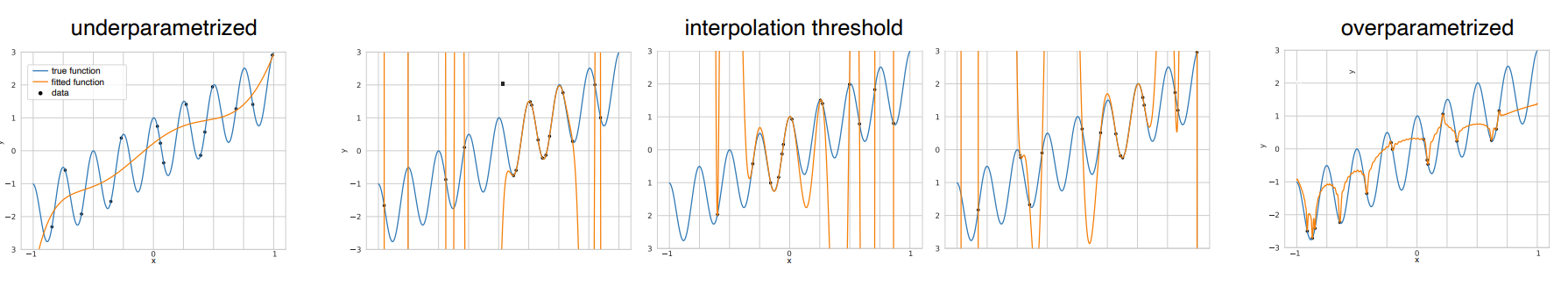

We can look at polynomial regression (trained via SGD) for a visual intuition (source):

Note that near the interpolation threshold, we can fit a curve through every point, but need huge oscillatory swings to do so, whereas with more parameters we can still exactly fit the training set, but can choose a simpler curve to do so.

Note that near the interpolation threshold, we can fit a curve through every point, but need huge oscillatory swings to do so, whereas with more parameters we can still exactly fit the training set, but can choose a simpler curve to do so.

Lottery Ticket Hypothesis

Another interesting empirical finding: if you perform the following procedure:

- Train a network, saving the random initialization.

- Use a pruning algorithm to remove the unimportant weights.

- Restart training for just that sub-network with the same random initialization.

It will probably converge to a network that performs at essentially the same level of error as the original network (and sometimes have lower test error). If you repeat this process on the sub-network, you can get to pretty high levels of pruning without increasing the error. For example, an MLP with dimensions $[784, 300, 100, 10]$ trained on MNIST, contains a sub-network of 21.1% of the original weights that can be re-trained to achieve lower test error with fewer training iterations, and a sub-network with only 3.6% of the weights remaining performs almost identical to the full network.

These sub-networks with great initializations are called "winning tickets."

How does this relate to the question of whether SGD has a bias towards simple solutions?

This potentially provides an explanation for why larger models have a better chance of finding a simple explanation than smaller models. It seems weird that models with more parameters will be able to find simpler explanations, but if there's something about the loss landscape in the larger network being more amenable to finding these explanations, it might make more sense.

Pruning, Distillation, Quantization

It's fairly well-known that neural networks retain most/all of their performance when you apply various lossy transformations:

- You can prune much of a network's weights without impacting the performance.

- You can distill a network into a much smaller student network without impacting the performance.

- You can quantize a network's parameters fairly aggressively without changing the output much.

That these practices seem to generally work could also be taken as evidence that SGD chooses simpler networks, as we would expect simpler networks to be more robust to these changes.

Other stuff

This is a catch-all section for bits that seem interesting but I didn't look at in too much detail.

- In the case of linear models, gradient descent on a least-squares loss starting from zero parameters is equivalent to using the pseudo-inverse, which finds a solution that minimizes L2 norm in the overparametrized case. Porting this to neural networks is tricky, but some stuff has been figured out, suggesting that SGD favors low-rank solutions at least some of the time.

- The low-hanging fruit prior idea claims that because SGD is driven by the gradient on the current batch of data, it operates greedily, finding solutions that are "incrementally better but not necessarily the simplest." This argues that SGD will choose networks that consist of many composable / parallel circuits instead of fewer simpler ones.

While this example is the algorithm that we use as humans, it doesn't necessarily follow that simple algorithms will be immediately human-understandable. In fact, I wouldn't be surprised if NNs are able to find solutions that are too simple for humans to have thought of.